Here at The Phree Press, we love all things free. Free food, free speech, and today’s topic:

A free market.

And there’s one free market that isn’t understood well enough.

The market for U.S. Treasury Bonds.

You see this market — just like all good free markets — deals in the realities of supply, demand, money, and time.

And in the age of so-called fake news, we as Americans need to stay grounded in reality.

Background

What exactly is a bond, anyway?

A bond is, at its most basic level, a loan1.

If you’ve ever loaned anything — a book, a sweatshirt, a pencil, money — you know there’s a real chance you might not get it back. Borrowers wanting to “forget” the loan is, unfortunately, only natural.

Because reneging on the loan is a real possibility, the borrower’s trustworthiness to repay the debt should be thoroughly evaluated by the investor2.

In this regard, the United States is a Lannister.

Ok well, maybe more of a trustworthy Stark than a shifty Lannister.

The point is, the U.S. federal government is super-duper trustworthy because the government has always paid its treasury debt. U.S. Treasury Bonds offer investors cream-of-the-crop stability tomorrow for their dollar today.

How a U.S. Treasury Bond comes into existence

In order to fund the federal government, the President first presents his ideal budget to Congress. Congress must then vote on and pass a budget bill.

Once the President signs the document, it becomes law.

If this law calls for more money to be spent than what will be recouped in taxes, the U.S. Treasury Department will need to sell bonds in an attempt to make up the deficit.

Important: The market where the U.S. Treasury sells directly to an investor is not the market we are talking about. This is known as the primary market.

The market we are talking about is the secondary market. The investor-to-investor market. In this market, one person wants to sell a U.S. Treasury bond he previously purchased, and another person wants to buy that bond. This market is but a small segment in the grandest investor-to-investor market of them all:

Wall Street.

The extra-special thing about the secondary market for U.S. Treasury Bonds

The really important thing to know about the secondary market is that it counterbalances itself.

You see, in this investor-to-investor market, if one investor decides to purchase a bond, it takes a bond off the market, which makes the bonds that are on the market more scarce and, in turn, more valuable. In economic terms, this can be put simply: the supply of bonds has decreased, making the existing bonds on the market more valuable.

Things that go up in value warrant a higher price. So the price to buy a bond from the market increases.

However, because bonds also have an interest rate attached to them, the higher price also needs to factor in the interest rate of the bond.

And because the initial price for a similar bond has increased, the effective interest rate necessary to attract an investor to purchase a similar bond has decreased.

Determining the ideal price to satisfy both buyer and seller is an inexact science.

Measuring and visualizing that price, however, is easy.

Enter the yield curve

In order to track the near-constant fluctuation of the initial prices and interest rates of similar bonds, the financial community has come up with a wonderful data-driven instrument: A yield curve3.

A yield curve is, more or less, a line graph.

On the Y-axis is the ever-important term “yield.” A bond’s “yield” is defined as “the return an investor realizes on a bond” and therefore factors in both the bond’s initial price and its interest rate. Higher yield = more overall money back to the investor.

On the X-axis is the amount of time an investor’s money will be “locked up” in the loan.

When you plot this data, it usually looks like a curve:

When it doesn’t look like a curve, the marketplace is indicating something is wrong.

And when the curve inverts, like it did this past March and again in the beginning of May, the marketplace is indicating something is very wrong.

Imagine, if you will, what a real-life physical marketplace would look like with an inverted yield curve.

a TriP To ThE BiZarre BaZaar

Let’s say you just found $100.

Instead of spending it on a new guitar or placing a foolish football bet, you decide to be a good capitalist and invest the money.

You also decide you really, really don’t want to lose the money, so you decide to invest in the safest possible investment there is:

A U.S. Treasury Bond.

So you go to the market and you meet a vendor selling a U.S. Treasury bond for a 2.5% yield over five years.

But then you overhear the vendor right next to him is selling the exact same product for a 3% yield over just two years.

“WHAT?!“ you would probably say to yourself. “Only a fool would buy the five-year bond! It is both a worse investment immediately and over time!”

And so you buy the two-year bond instead, and walk away from the marketplace feeling like you just got the deal of the century because there is absolutely zero reason the safest investment in the world would offer less money over more time.

…right?

What the market knows that you don’t

A central theme to this blog post is that “the market is the market” and it can never be wrong.

This is because a market has no bias. It has no agenda. It is simply a place where both buyers and sellers converge to exchange items for a price they both think is fair. The market is omniscient and speaks only truth via data. And because this data represents all buyers and sellers, it represents the majority.

So why would the majority of investors think U.S. treasury bonds are going to decrease in value over time?

“Investors will settle for lower yields associated with longer-term low-risk government-issued debt if they think the country’s economy will enter a recession in the near future.”

A recession?!

Yes. A recession.

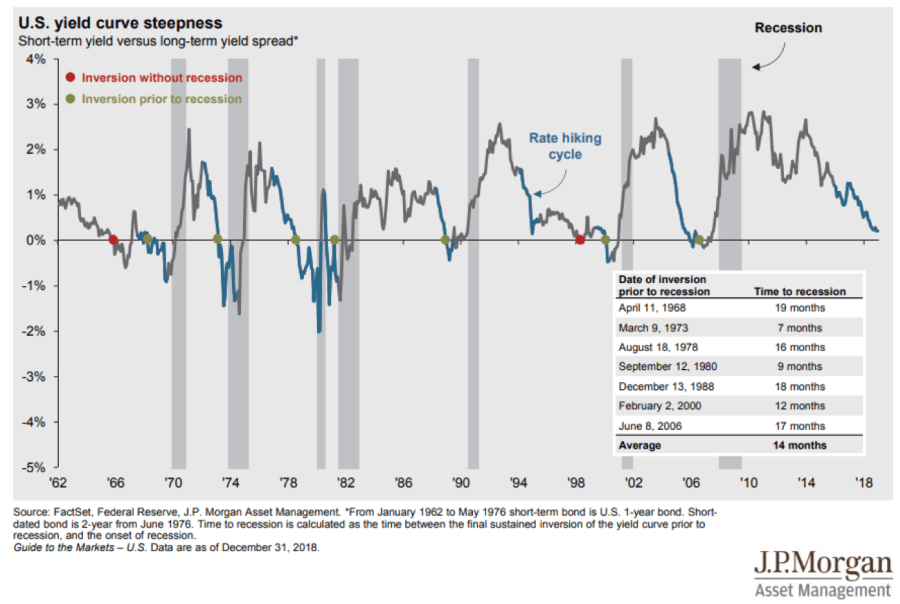

In fact, the data supports that an inverted yield curve more often than not precedes a recession:

But it’s OK because recessions — much like wanting to default — are only natural.

However, unlike other classic recession indicators, there’s something special about when the yield curve inverts.

Other indicators are, mostly, just numbers. Just data. But the yield curve inverting is a reaction created by investors analyzing all of that data and betting that a recession is incoming. The yield curve inverting is a dollar-and-data-driven response by investors based on their analysis.

That’s what separates it from other classic recession indicators.

Parting words – recessions, government, and continuing the natural order

Truly I hope that investors are wrong and a recession isn’t imminent.

If you remember the last recession, you remember an absolutely awful time. This is because it wasn’t just a recession, it was a full-blown financial crisis brought upon by fiscal irresponsibility of both borrowers and lenders. Congress and the Federal Reserve responded to the damaging effects of this financial crisis in unprecedented fashion.

However, the reality that the yield curve is inverted should not be ignored. Humans are not ostriches nor should we act like them.

So the only logical thing for the U.S. government and its citizens to do is to stay keenly aware of this reality and begin to prepare for the next downturn.

Hopefully we learned some lessons about fiscal irresponsibility and that the crisis-driven regulations requiring banks to undergo annual stress tests are adequate enough to mitigate the severity of the next downturn.

However if the U.S. and its people – independent of government intervention – are unable to pull ourselves out of this prophesied recession, my advice is to get comfortable with electing federal politicians who want to: a) increase government spending in areas that are important to you and that will stimulate economic growth and b) cut tax rates in areas that are important to you and will stimulate economic growth.

Because increasing government spending and/or cutting taxes in response to a recession is, of course, only natural.

In the meantime, keep an eye on the financial/economic news (especially what the federal reserve is doing!) in relation to its concurrence/divergence from the business cycle, form your own opinions, and prepare accordingly.

Footnotes

1The issuer of the bond (a.k.a. the borrower) needs money in the short-term. The issuer will pay back the exact amount of money needed (a.k.a. the principal), along with an additional agreed-upon amount of extra money (a.k.a. interest) at an agreed-upon time to the lender of the money (a.k.a. the investor). Add paperwork and signatures and, voila, the lender receives a certificate (a.k.a. bond) that ultimately holds the borrower accountable in a court of law for repaying both the principal and the interest at the agreed-upon time should the borrower renege (a.k.a. default).Go back to where you left off

2Side note: this level of trustworthiness is often directly reflected and objectively measured by the interest rate of the loan/bond. We as consumers are most familiar with this idea of trustworthiness and interest rates having a definitive correlation via our credit score. Bad credit score = low probability to repay the loan = high interest rate, and on the other side of the coin, good credit score = high probability to repay the loan = low interest rateGo back to where you left off

3When referring to the specific secondary market of U.S. Treasury Bonds, it’s colloquially known as the yield curve. Go back to where you left off