Ray Toreson is a 91-year-old Chico citizen and World War II veteran. Toreson decided to enlist in the Army Air Core at age 20, and his memories of war time are not to be missed, as they’ve helped define his image as a man’s man. This is his story.

- War in the Pacific – Cheap thrills, close calls and tainted whiskey.

- “I still don’t buy anything Japanese.”

- Back home – the doctor, the teacher and The Chronicle.

- He’s a man’s man, man.

Walfred “Ray” Toreson was operating a Caterpillar in Vina when he got the news. His two-years-younger brother, a “big and husky” fellow who captained both the football and basketball teams, had just joined the military.

And he was about to have a “short and fat” companion.

“I gave the guy I was working for two weeks to get somebody to replace me,” Toreson says. “Then I went in.”

Ray Toreson’s life changed drastically when he decided to join the military and look after his brother, Howard, in 1940. Filled with long plane rides, battle, and occasional horseplay, his days in the Army helped to define a remarkable life.

He wasn’t your typical army soldier. Instead of accepting an assigned position in an infantry unit, Toreson joined the Army Air Corps, a sub-division that later became the US Air Force. He had harbored a desire to fly since his teenage years, when he first barnstormed over Alturas, his hometown in northeastern California.

In those days, “barnstorming” pilots took paying passengers on short sightseeing flights, usually over small towns and sparsely populated areas.

Toreson enjoyed when pilots went barnstorming in small towns like Alturas because, before World War II, airplanes were fairly uncommon.

“They’d take off, circle the town, come in and land. Five bucks,” he says. “That was a lot of money in those days.”

Considering he was earning 50 cents an hour working at the sawmill in Alturas, it was a very substantial amount of money.

Toreson felt that his barnstorming experience quickly impacted his military career. Very soon, the Air Corps assigned him to a balloon squad, flying a small blimp to spot military targets.

These small blimps, called Caquots, averaged 92’ x 32’ and, according to Military.com, could fly to heights of 4,000’.

But then Pearl Harbor was bombed Dec. 7, 1941.

Toreson was training the coast guard how to handle the tiny blimps, he says. The military then decided to build larger aircrafts, and all of the troops in his squadron, him included, were transferred to a bomb group.

“We had to completely retrain them in everything because they just completely done away with the blimp outfit,” Toreson says. “Too slow to provide any use.”

He was then transferred to England, but the memories of England don’t compare to those of Guam, where he was transferred in the fall 1944.

War in the Pacific – Cheap thrills, close calls and tainted whiskey

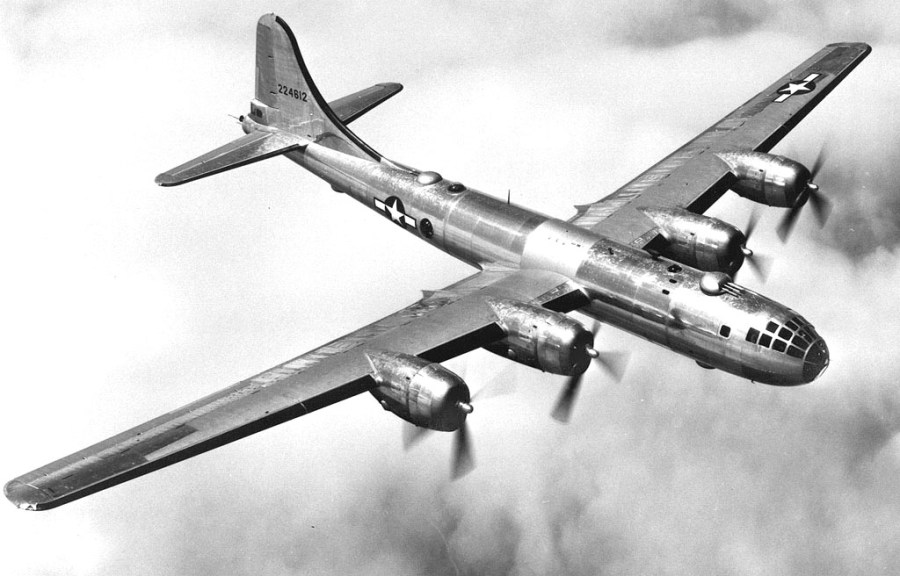

“We flew a B-29, that was the largest airplane made in the world at that time,” he recalls of the infamous American plane nicknamed the “Superfortress.”

The plane weighed 72 tons, had a 141 foot wing span, was nearly 30 feet tall and was only a foot shy of being 100 feet long, according to Aviation-History.com.

Toreson was assigned the plane’s tail gunner position, a necessary part in his 11-man flight crew. In fact, the tail gunner is thought to have brought down 75 percent of all enemy planes destroyed by B-29s, according to Aviation-History.com

He remembers a lot about his 33 combat missions, particularly the fun and games he and his fellow crew members would engage in.

One of Toreson’s crew members, the radar operator, would constantly fall asleep in front of the radar. Eventually, the plane’s navigator got sick of it, and asked Toreson what he thought they should do with him.

“I said ‘I think we really ought to wake him up,’” he recalls.

The navigator then flipped a switch on the dashboard, and left it flipped for a solid minute, Toreson says. Once the navigator flipped it back into position, the plane dropped a large number of feet in the air, knocking the sleeping radar operator out of his stool.

The radar operator then rushed over to the window, and was relieved, albeit a little mad, to see nothing but blue sky all around him.

“He slept more than any man I ever saw,” Toreson says. “But we had a lot of fun with him, horsing around and all that.”

The 12 to 15 hour-long flights from Guam to Japan were filled with plenty of time for horsing around, but there were also times when enemy planes tried to shoot Toreson and his crew down.

During one mission, the plane was leaking gasoline and had so many bullet holes in it, the pilot had to make an emergency landing on the newly captured island of Iwo Jima.

While the plane was being fixed by military mechanics, Toreson and his crew just had to wait it out, he says. During the down time, Toreson climbed Mt. Suribachi, the spot where the historic American flag raising occurred.

After three days of repairs, Toreson was happy to see the plane fixed, but surprised to hear just how bad the damage was.

“It had 250 holes in it,” he remembers.

After having 250 bullets shot into your plane, it’s no wonder Toreson and his crew had a doctor visit them after every mission.

Once a mission was over, each person on the aircraft had to go into separate rooms to be interrogated by higher ranking officers on what they saw, Toreson says.

After the interrogation was over, a doctor would come out with a bottle of whiskey laced with sleeping powder, and pour the interrogated person a 2 ounce shot.

“They said it’ll settle our nerves down,” Toreson says, his voice dropping in volume as he reminisces. “Quiet us down.”

“I still don’t buy anything Japanese.”

Right after the war started, Toreson wrote a letter to his brother, Howard, just to check-up on him.

“I got the letter back, and it said ‘service suspended,’” Toreson says. “In other words, the military knew they couldn’t get mail to the Philippines.”

Toreson just had to wait it out until he heard something from his brother. Eventually, a few months passed, then a few years.

The war ended in August of 1945 and he still hadn’t heard from Howard, but Toreson’s mother received a very different kind of letter from the U.S. government.

According to the letter, Howard Vincil Toreson was captured by Japanese soldiers when they invaded and took control of the Philippine Islands in 1942.

After he was captured, he was made part of the Bataan Death March, the historic World War II event where Japanese soldiers marched 90,000 to 100,000 Filipino and American prisoners of war 63 miles to another military base.

Some 7,000 to 10,000 prisoners died along the way, and Howard was, unfortunately, one of them, Toreson says. The letter states the official cause of death as malnutrition, but Toreson views it much differently.

“They starved him to death,” Toreson says with a mixture of sadness, stoicism and resentment. “Evil Japanese.”

“He’s the only brother I had,” Toreson says as the outside corners of his eyes begin to fill with tears. “I went in because he went in.”

“That’s why I don’t buy Japanese cars,” he says. “I don’t buy Japanese anything.”

Back home – the doctor, the teacher and The Chronicle

After the war, Toreson came back to Northern California and moved to Willows, where he managed a service station he leased from Shell in order to make a living, he says.

In 1947, he married a young lady from Omaha named Margret Polson who he met through one of his friends in the army, he says. Together they had two children, and although Margret wished she had two girls, both turned out male.

Margret wasn’t ready for boys, so when time came to name each of them, she picked names she saw in the San Francisco Chronicle on their birthdays, she says. Neal and Ricky Lee.

“I was kind of disgusted because I didn’t get any girls,” she says with a chuckle.

Despite Margret’s wish, the Toresons raised two sons. Neal now works in physical therapy at Enloe Medical Center, and Ricky teaches high school in Crescent City.

Ray Toreson was just happy he was able to send both of them to college, something he never really had the time or money to do, he says.

“See in those days they didn’t have grants and stuff to put you through school if you needed it,” he says.

Although Toreson never went to college, he didn’t mind being in the service, and he came pretty close to re-enlisting, he says.

Ultimately, Ray Toreson is the picture perfect image of a man’s man. He enjoys New York steaks, fishing in the summer, country-western music and still has a powerful knuckle-squishing handshake even at age 91.

“I thought that was the greatest thing, you know. Go out and work with a bunch of men,” he remembers of his days in the service and at the sawmill.

And with a little luck and a lot of faith, Toreson might just get to experience another life filled with happiness and brotherhood.

With his brother, Howard, alongside.